Joining PNWA connects you to a vital community of writers. Our mission is to develop writing talent from pen to publication through education, events, accessibility to the publishing industry and great member benefits

Editor’s Blog

I collect stories of artists who’ve been told by industry professionals that their novel, or their play, or their song just isn’t what people are looking for.

When you’re feeling as if all this writing is for nothing, when it seems like everything sent out to the world disappears like smoke in an empty forest, go back to the source.

There are plenty of times when I’m writing a song or story where I feel stuck with the thing. I have half of it, but I can’t find the rest, as if I’ve followed my GPS to a dark dead-end. At some point, however, I breakthrough and I see the other side.

A year ago, our cat Birdie, while keeping us company in the bathroom as we completed our evening ablutions, noticed a single silver fish slithering along the grout between the floor tiles by the bathtub.

Shoes and stories and acting styles are all aesthetics of one sort or another. Word choices too.

You also can’t believe some people get good ideas and some people don’t. Maybe you’re one of the “unlucky” ones to whom inspiration is doled out in meager doses. What’s to be done then but complain and envy others?

I was taking questions at the end of a class years ago when a gloomy fellow at the back of the room raised his hand. “My problem with writing,” he said, “is the selling and marketing of my stories. I don’t do this to prostitute myself.”

I told him I had nothing but confidence in him, but that he had to make sure to write like Chris, and not to try to write like Salinger or Joyce or Hemingway. That should be easy for a natural storyteller like him, but I knew how people could get in their own way.

Interviews

Travis Baldree is a full-time audiobook narrator who has lent his voice to hundreds of stories. Before that, he spent decades designing and building video games like Torchlight, Rebel Galaxy, and Fate. Apparently, he now also writes #1 New York Times bestselling books. He lives in the Pacific Northwest.

Tara Moss is an internationally bestselling author, human rights activist, documentary and podcast host, and model. Her crime novels have been published in nineteen countries and thirteen languages, and her memoir, The Fictional Woman, was a #1 international bestseller.

Stephen Greenblatt is Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University. He has written extensively on English Renaissance literature and acts as general editor of The Norton Anthology of English Literature and The Norton Shakespeare. He is the author of fifteen books, including The Swerve, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award, and Will in the World, a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Dark Renaissance is his latest.

Sue William Silverman is an award-winning author known for her fearless explorations of trauma, identity, and personal transformation. Her latest book, “Selected Misdemeanors: Essays at the Mercy of the Reader,” showcases her signature blend of lyricism, insight, and unflinching honesty.

Bernice L. McFadden is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Tulane University and the author of several critically acclaimed novels, including Sugar, The Warmest December, Loving Donovan, Nowhere Is a Place, Glorious, Gathering of Waters (a New York Times Editors' Choice and one of the 100 Notable Books of 2012), The Book of Harlan (winner of a 2017 American Book Award and the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work, Fiction), and Praise Song for the Butterflies (long-listed for the 2019 Women’s Prize for Fiction).

Kate Russo, author of Until Alison and Super Host, grew up in Maine but now divides her time between Maine and the UK. She has an MFA in painting from the Slade School of Fine Art, and while living in London, she worked with the theatre group, Love Bites, who presented two of her short plays (“The Blind” and “Bernie's Night Off”) at the Calder Bookshop Theatre. She exhibits widely in the United States and England. Learn more at KateRusso.com and connect on Instagram @RussoKate.

Jane Friedman has spent her entire career working in the publishing industry, with a focus on business reporting and author education. Established in 2015, her newsletter The Bottom Line provides nuanced market intelligence to thousands of authors and industry professionals; in 2023, she was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World. Jane’s expertise regularly features in major media outlets such as The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Today Show, Wired, Fox News, and BBC

Megan Abbott is the Edgar-winning author of the novels Beware the Woman, The Turnout, Give Me Your Hand, You Will Know Me, The Fever, Dare Me, The End of Everything, Bury Me Deep, Queenpin, The Song Is You and Die a Little. Her most recent is El Dorado Drive.

Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Salon, the Guardian, Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times Magazine, and The Believer. Her stories have appeared in multiple collections, including the Best American Mystery Stories of 2014 and 2016.

NELL JOSLIN is a native of Raleigh, North Carolina and received her MFA from North Carolina State University. Besides a fiction writer, she has been a public school teacher, medical librarian, copy editor, freelance journalist, stay-at-home mom, and attorney (although not all at the same time). She currently lives in Raleigh. Find her online at measureofdevotion.com

Nancy Kricorian, who was born and raised in the Armenian community of Watertown, Massachusetts, is the author of four novels about post- genocide Armenian diaspora experience, including Zabelle, which was translated into seven languages, was adapted as a play, and has been continuously in print since 1998. Her essays and poems have appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly, Guernica, Parnassus, Minnesota Review, The Mississippi Review, and other journals.

Articles

The relentless click-click-click of a metronome may be helpful for practicing finger exercises, but it’s deathly dull for an audience. Classical composers use Italian terms to signal changes in the desired pace of their music, such as lento (slow), allegro (lively), and presto (very fast). My favorite of these is rubato, literally “robbed” time, meaning the performer is free to “rob” a moment from one note and give it to the next.

We often speak of a writer’s voice, that distinct and resonant quality that separates one narrative from another on a crowded shelf. We talk of plot, of structure, of the muscularity of good prose. These are the tools of our trade, the timber and nails of the houses we build for our stories.

Today, in 2026, when someone hears my accent and asks where I’m from, I hesitate. I lower my eyes, give a small smile, and say, “I was born and raised in St. Petersburg, Russia.” I hear the words and feel a pinch of embarrassment. I don’t always want to explain the Russia I knew—my Russia—because it feels so different from the Russia people picture today.

But things were very different in 1993. That was the year I moved, by a rather unlikely twist of fate, from St. Petersburg to a small college town with a surprising name: Moscow… Moscow, Idaho.

What makes your writing unique? When readers come across your books, what do they see that makes them know it’s yours?

Establishing your position within the writing community can feel impossible, especially if you are just beginning your career. Each writer you come across pulls you in different directions, which can make it challenging to find your creative identity. The tendency to adopt the stylistic elements of a recently read work is a natural part of writing, one that contributes to your emerging voice.

As a judge for the popular storytelling platform NYC Midnight, I read a lot of flash fiction and microfiction submissions. For the unfamiliar, flash fiction is loosely defined as a short story of up to 1,000 words. Microfiction is a subset of flash fiction, with stories weighing in at 100 words or less.

When I first began freelancing, it could get lonely. It was not like other jobs where you have coworkers with whom to bounce ideas off or solve problems, but writers need watering holes, too. Sometimes there is no one else that understands what you’re going through better than those who have been through it as well

I groaned as my high school English teacher told the class that our senior research papers needed to include an outline. I loved writing; I hated outlines. Since I ended up writing never looked anything like the outline I created at the beginning of the assignment, I often wrote the paper first and then created the framework page she required.

Driving down I-75 in Atlanta, a billboard blared: “Your Wife Is Hot! And she’s getting hotter!” In smaller print, the sign advertised an air conditioning company. I found the innuendo worth pondering. The writerly side of me mulled over creating a flash fiction on the double-entendre of “hotness.” I’d begin by saying Leroy’s wife was leaving him because after all she was much HOTTER than poor Leroy. When you read on, you’d find, the Mrs. was leaving her conjugal nest, not for another fella, but for her mom’s house where the AC worked. This is how a nugget of an idea mushrooms into a vignette! Surprise twists make stories interesting.

In 2021, I set out to write a book that had slowly been forming in my head for years. I work in creating affordable housing, and I’d always wanted a book I could leave behind with community groups, policymakers, and the like. Developing affordable housing is complicated and full of obscure jargon, but it’s all learnable. I wanted to write a book that would demystify what affordable housing is, how it works, what we’ve tried, and what is necessary to fix this housing crisis.

When I first buckled down to seriously pursue my writing journey in my mid-20s, I had no intention of writing short stories. I wanted to pen the next great fantasy series, something akin to George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire or Joe Abercrombie's The First Law Trilogy. What I discovered is that such series are tremendously difficult to create, especially as a newbie. Nevertheless, I persevered, and my writing improved, albeit at a slow rate.

Inspiration

Tom Rob Smith, Jamie Ford, Nicola Griffith, Jussi Adler-Olsen, and Stella Cameron on why stories matter.

Ingrid Ricks, Theo Pauline Nestor, Katie Hafner, and Gregory Martin discuss the challenges of writing memoir.

Lessons learned from the writing life, featuring Cheryl Strayed, Elizabeth George, Thirty Umrigar, Deb Caletti, and more . . .

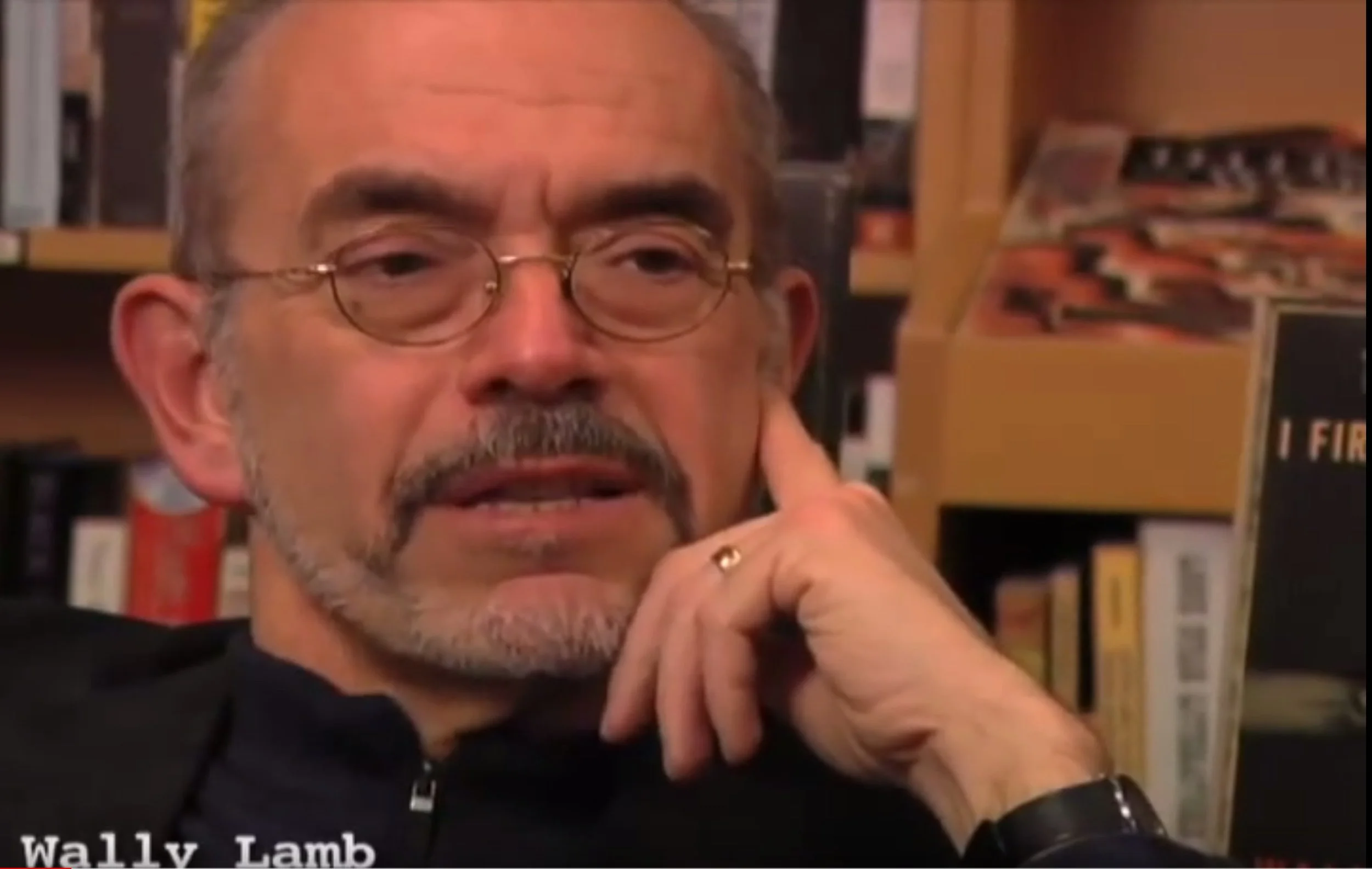

Advice and inspiration from Wally Lamb, Clive Clussler, Lee Child, Stephanie Kallos, and more.

Inspiring advice from Sir Ken Robinson, Yann Martel, Gary Zukav, Andre Dubus III, and more.

The question, then, is not what you will experience, but the story you will tell yourself about those experiences.