Your Story Needs a Hook, but Your Characters Are the Bait

by Jason Black

Illustration by Jennifer Paros - Copyright 2010

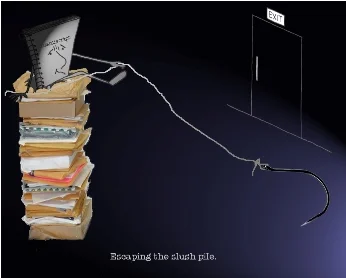

Ask anyone in the publishing industry—agents, editors, sales reps—and they’ll all agree your novel must open with a strong hook. You'll never escape the slushpile without one. If you ask them what that means, you'll probably get an answer like, “It has to pull readers right in, grab them by the shirt collar, and make them want to read the next page.”

Translated into advice you can actually use, here's what they're trying to tell you: A great hook shows character through conflict.

That's the trick. A story needs a good hook—usually a dramatic, page-one situation brimming with conflict—but the hook needs bait or nobody's going to care. Your characters are the bait.

Conflict makes an effective hook because it drives the reader’s curiosity: What’s the conflict about? What’s at stake? And most importantly, what's going to happen next?

"What happens next" is paramount because it reveals your characters. After all, a story doesn't move until the characters move it. Nothing happens next unless the characters start making choices and taking actions.

Nothing happens until they face that conflict.

Want to know a secret? The best way to turbo-charge your novel's opening is to combine conflict with choices and actions that reveal your characters for who they are: Nothing shows what somebody is really made of like watching them respond in a crisis.

Here are four steps to creating a killer opening hook:

First, find the conflict. Find the moment in time nearest to the beginning of the story when there is a high-point of conflict. Don't worry if this is in chapter three of your draft: Good news, you can cut chapters one and two which are probably just boring setup anyway. Presto, that's two less chapters you have to work on in revision.

If your exciting moment happens before the book opens, consider pulling the opening of the book back to that moment even if it means adding a chapter or two to bridge between that opening and the rest of your story. When the result is a compelling, character-based hook, it's totally worth it.

Second, look at who is in the scene. Who is involved in the conflict? Who or what are they facing? What do your protagonists need to accomplish to overcome the conflict, or at least to escape the scene? Now ask yourself how they would set about accomplishing that task. Would they charge right in? Would they act, but only reluctantly? Would they try to talk someone else into dealing with the situation?

Put your protagonists in a crisis, and force them to show their true colors. If your antagonists are also in the scene, do the same thing for them. Find those choices and actions which are consistent with each person's goal, personality, and abilities.

Third, create opportunities for the characters—and especially your protagonists—to display their personalities and abilities in action. If your protagonists are driving the scene, you're probably already doing this. But if your scene is driving your protagonist, if they're watching events unfold without attempting to alter them, then you've got a problem. When your characters don't act on their goals, readers will wonder why not. Make your characters drive the scene.

Fourth, make readers care about your characters. If you've done steps one through three right, you'll have set up the novel's central conflict, gotten the story rolling, and shown readers who they're supposed to care about and why. But you still have to make them care.

Care comes from feelings of sympathy or empathy, so show your characters facing difficult obstacles, ones which push their abilities. Easy challenges lack drama; giving characters tasks which are old-hat to them doesn't show much about their personalities.

Consider failure, too. Don't be afraid to make the challenge too difficult. Letting your protagonists fail in the opening scene can be wonderfully dramatic. It shows readers how your characters respond to failure, which is itself deeply telling as to what kind of people they are. Do they beat themselves up about it? Do they brush off the failure as though it didn't happen, learning nothing? Or do they pay attention so they can do better next time? Readers love to root for the underdog; a great way to portray your protagonists that way in your opening is to let them fail at something significant.

The slushpile is full of manuscripts that have no hook at all. Ones that open with some of the most boring situations imaginable: People waking up in the morning, walking down the street, going about ordinary, day-to-day activities. Don’t do that. Somewhere in your plot is a conflicted, pivotal event that gets the main storyline going. Find it, and put it on page one.

The slushpile is equally full of manuscripts that open with conflict but haven't baited that hook with the story's characters. These manuscripts resolve the conflict without showing anything meaningful about the characters. As long as you're putting conflict on page one, make your characters face it there too.

Novels that don't have a great hook will never escape the slushpile. How does yours stack up? You've cast your line. Your hook is in the water. But if you want an agent or editor to bite, you'd better be using your characters as bait.

Jason Black is a freelance book editor who actively blogs about character development. He recently appeared as a book doctor at the 2009 PNWA Summer Writers Conference. To learn more about Jason, visit his website at www.plottopunctuation.com