Rest, Peace & Relaxation: Discovering the Power of Passivity

by Jennifer Paros

“The time to relax is when you don’t have time for it.”

One morning while taking a vitamin, I inhaled in a peculiar fashion, creating a sudden suction that pulled the capsule back and lodged it in my throat. I tried swallowing and drinking to no avail, but only really understood the severity of the situation when I attempted to breathe more fully and heard airy whistling sounds, then attempted to talk and found I could not. At that point I reflected upon my understanding of the self-Heimlich maneuver, which was scant. Once I realized I could still breathe enough, I knew I needed to be passive, though I wanted to actively help myself. I became still and aimed my attention on a state of mental passivity – a neutral place of no reaction and no judgment. More than just the old “Don’t panic” directive, I wanted to intentionally rest in a state that was peaceful even though the situation was not. Within the next few minutes, I had the impulse to manipulate my throat with my fingers (something I’d tried earlier) and the pill dislodged. My full breath returned along with my voice.

Most of us are so concerned with taking action we often reject the role passivity plays in effective action. When we’re not putting pressure on ourselves to do something, we’re often thinking we’re not doing enough. But a certain kind of passivity is a part of the receptiveness needed for progress and productivity. Passivity – a maligned and often disgraced state of being – actually plays an important role in locating a peacefulness that aids in the resolution of our problems.

French pharmacist and psychologist, Émile Coué (1847-1926) taught passivity to help his clients receive new ideas and improve their wellbeing. Knowledgeable in hypnotherapy and known for the autosuggestion, “Every day in every way, I am getting better and better,” Coué believed the imagination to be more powerful than the will. He described how when a wooden beam is laid on the ground, most everyone can walk across, but if the beam suspended between two buildings, virtually no one could. To Coué this demonstrated that imagination (in this case imagining falling) is more influential than the determined effort of the will (determining to walk across). With much success, he taught his clients to purposefully direct their imaginations, believing our bodily (health), mental, and emotional responses can’t but be cued by the pictures and projected thoughts we imagine. Coué found that when the mental state in which the effort and strain of the will are set aside, the mind was made ready for receiving new, improved ideas to which his patients responded and got better.

“With every year of playing, you want to relax one more muscle. Why? Because the more tense you are, the less you can hear.”

When I was little, my parents owned a white station wagon. It was large, functional, and severely unglamorous. Beyond the backseat was the area we called the “back-back” – the back behind the back. When we took road trips, an old foam mattress was placed in the back-back where I would curl up with my favorite blanket and pillow. I was carried, rocked, transported, comforted, and left peacefully alone. Sometimes I slept but mostly I just enjoyed the ride. I was as relaxed as I could be. There was joy in being a passenger, moved by something other than just my own will. I was happy setting my mind to no particular task, yet simultaneously allowing myself to be carried forward.

Our minds are in perpetual and often habitual activity. Sometimes we engage less aggressively with that activity, and sometimes more – concerning ourselves with almost every thought that blows by. Often when we are aggressively pursuant of thoughts, worried about projected scenarios, we’ve got ourselves convinced it’s all very important. But when fixated on importance, it becomes harder for us to relax enough to find our way to solutions. That’s where mental passivity, a willingness to allow our attention to be less reactive to our thoughts, becomes so relevant.

I like to think I don’t need to choke on a vitamin nor be wrapped in a blanket and carted about to remember how to relax. I only have to acknowledge that taking action involves more than just moving things around. There are thoughts and feelings that influence those moves, and the energy generated from our imaginations that carries us forward.

May we all be passive enough to receive, at ease enough to be carried, and relaxed enough to appreciate the ride we’re being given.

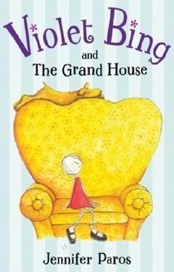

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.