Put Yourself in the Middle of it All: There is Nothing to Lose

by Jennifer Paros

“You will either step forward into growth or you will step back into safety.”

For a few years when I was little my family took summer trips to Martha’s Vineyard. We rented a tiny cabin and walked to the beach every day. I loved all of it, but was intimidated by the waves, which could get pretty big sometimes. Going under them or turning to ride them required me to be in the middle of the action – which was not my habit. And my reticence to participate positioned me perfectly for being knocked down. Reckless or risky behavior is usually considered the cause of trouble, but in this case, caution caused my troubles. I was trying to avoid danger and often ended up underwater, overwhelmed, and out of control.

We teach each other to be careful, to have forethought and to assess, but the application of that advice can become distorted and leave us perceiving more risk in life than is real. The belief that we are at risk naturally creates resistance, and then we feel stuck and overwhelmed. But most of the time, there is no danger, nothing to lose, just fear of possibly feeling bad. Focusing on potential loss logically makes us insecure. Measuring what we could lose rather than purposefully engaging in what we want to create generates more problems than it prevents.

When I am writing, there are many activated parts and pieces of which I am aware – ideas, characters, emotional components, storylines.If I fixate on what I have yet to do, understand, or “get right”, I see failure and become resistant to the project.If I take my place at the center of the process, situating myself (mentally and emotionally) in the “middle” of the unfolding, I see the next step.Sometimes I have to remind myself that there’s nothing to lose in taking a swing at writing a scene or a new chapter. By not judging, assessing, measuring, or comparing, the development of my idea is allowed to be what it is in the moment and to progress – and the unknowns cease to be a cause for distress.

“It is only when the mind refuses to flow with life, and gets stuck at the banks, that it becomes a problem.”

Several years ago, my son wanted to build his own computer. We ordered the parts and as each one arrived, he was so excited he hugged the boxes. We’d intended for someone to show him how to build the computer, but soon it was clear he intended to do it unassisted. It was about a thousand dollars worth of components, some of which were quite delicate. When everything had arrived, he brought it all to his room, hung a Do Not Disturb sign on the door, closed it, locked it, and began. My husband and I looked at each other nervously, half expecting the computer to be assembled magically in record time, half expecting utter chaos.

Partway through, our son emerged, shaken. He’d done something – gotten the stuff from the tube on a part he shouldn’t have (“It might be ruined,” he moaned.), was confused about this and that and generally, profoundly overwhelmed. I walked into his room - a field of opened packaging and boxes, ignored instructions, tiny parts and pieces on the floor and bed (some seemingly rolling away), our laptop open and paused on a YouTube tutorial on how to build a computer. I suppressed any reaction. His eyes were tear-filled, his face flushed, he’d determined himself and his efforts a failure. We talked; he calmed down some and I suggested he take a break. He was appreciative, rejected the break idea, closed his door, and went back to work. Several hours later, the computer was complete and running. He had given over to the process, placed himself in the middle of it all, stopped doubting the path, and allowed himself to find his way.

When we judge our ability and what we’re doing, we take ourselves out of the game; we remove ourselves from the development of the moment and our own creations. Ideas, insights, and paths come from being in the middle of it, not from standing on the outside looking in. The process is the unfolding of what we want, not a grind we have to get through. If we look at what we want as out there, we cannot see it as already under way, happening now, as available to us as we are ready to participate in it.

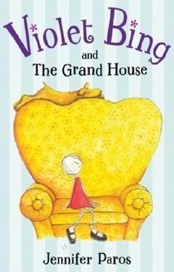

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.