Freedom From and Freedom To: On Quitting, Showing Up, and Getting Ready

Jennifer Paros

“We must be free not because we claim freedom, but because we practice it. ”

I was lying in bed the other night unable to sleep. My right leg was aching so intently I couldn’t seem to pull my attention from it. I had injured a muscle, hadn’t realized it was much of anything, but gradually discovered it was something. My leg seemed to want to move, yet any attempt at movement increased the pain. After two hours of trying to fall back to sleep, I decided to get up. Supporting my troubled leg, I hoisted it out of bed, placed it gently on the floor and hobbled from the bedroom, giving into to both the insomnia and the discomfort. The next day, I whined and limped, angry I’d somehow done this to myself, and angry at the condition for getting in my way.

After a couple days spent shaking my fists at the gods as both my mobility and frame of mind became increasingly compromised, I realized I had to give up. Not give up on getting better – give up on fighting. I was mentally flailing, unwilling to give myself a moment’s peace. I needed to stop. In order to allow my body to restore itself, I had to stop interfering; and I came to understand that my mental resistance was the interference.

The next time I attempted sleep, I was clearer on what my job was: I had to calm down – to be as still as possible, to let my body and being sink into that bed the way a stone would sink to the bottom of a pond. My job was not to get rid of the pain, but rather to fight nothing, worry about nothing, judge nothing. Once I realized it was my fear of and concern about the pain that was keeping me awake more than the pain itself, I was able to stop worrying long enough to fall asleep.

I wanted freedom and the pain seemed to be in my way. I thought my experience was jailing me. But then I realized I was still free, just not purposefully using my freedom. I was having knee-jerk reactions to a condition and, in doing so, I was living on the surface of my ability to respond. There is no freedom in reactiveness. The “prisons”, the “jailers”, the things seemingly in our way – none of these can be fixated on if we wish to move beyond them.

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

I work out almost every day, but with my leg in disorder I couldn’t do much. Nevertheless, I put my exercise clothes on each morning. Though logically it seemed pointless, after several days, I understood that I was making myself ready for what I wanted. If I can’t run it, I might walk it; if I can’t walk it, I might think it and/or feel it; regardless, I can make myself ready for it. There is always a way to show up for what we want, but we have to be willing. And showing up, of its own accord, is satisfying and freeing. There is much more to being free than being able to take a particular action at a particular time, and much more to freedom than being able to control conditions.

I was thirteen when I returned to taking piano lessons after being away from it for years. I was enjoying practicing and excited to be playing more difficult pieces. But my teacher soon discovered my incomplete grasp of some fundamentals and assigned me much easier music to strengthen my skills. The faulty foundation from which I’d been progressing could only ultimately limit me. To my own dismay, I quit. I walked away from something I wanted because I felt ashamed of my current limitations. I would not use the freedom I did have to ready myself for greater freedom.

As my leg recovers, I find myself wondering what I want to do with my mobility once it fully returns. Once freedom from the pain and limitation is gained, what do I want to use freedom to for? It’s not enough just to be able to return to doing the usual things in the usual way. Our sense of freedom depends upon our willingness to use it. Regardless of perceived limitations, there is always a way to show up for what we want, in order to make ourselves ready for it. And when we do, we are truly free.

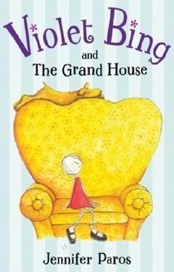

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.