How Do I Stop Scaring Myself?: Choosing a New Premise for Our Stories and Our Lives

Jennifer Paros

“Of all the liars in the world, sometimes the worst are your own fears.”

My mother was five years old, almost six, when she became so ill she was taken to the hospital in an ambulance; she had contracted polio. It would be another ten years, around 1953, before the vaccine would be made available. In the 1940’s and 50’s, polio was peaking and understandably there was a lot of fear of the risk of paralysis and possibly death. But my mom doesn’t remember being frightened or missing her parents while in the hospital during her quarantine. She felt cared for, she felt safe, and the effects of the polio eventually faded and her body recuperated. Her mother, on the other hand, suffered exhaustion for many months afterwards. The emotional toll had been great. My mother actually lived the experience; while her mother lived through a projection of what might happen – a projection that frightened her so much, it left her depleted.

When I was eight I was so frightened of school the only thing I wanted was not to feel so afraid any more. I locked myself in the bathroom, I hid, I even jumped out of a (slowly) moving car to try to escape going to school. One night I slept under my bed, on the wooden floor, without a blanket or pillow so the bed would appear unused and give the illusion I had left. At age five, my mother had a logical reason to be frightened – separated from her parents, in a hospital by herself. Objectively, at age eight, I did not. Yet I was terrified and she wasn’t. But my mother’s premise was that she was safe, her life was good, and people were taking care of her. I was operating from another premise.

The premise of a story creates the foundation for the story, and the characters’ responses, actions and emotions. Premises structure the realities we are creating, whether in fiction or in life. This is why an author can write a realistic, believable story about someone who endures a dramatic event who is not traumatized by it, as well as someone who is traumatized by it. If the character is well crafted, we understand her point of view and the premise from which she is working, and therefore why she responds to her world the way she does. The psychological platform from which a character operates allows us to accept the reality she’s experiencing even if it’s at variance with facts.

“Every human is an artist. And this is the main art that we have: the creation of our story.”

One of the nice things about getting scared out of your wits is that useful questions arise, like: “How did I get there? And if I ever get there again, how do I get out?” Over time, as I came to understand nothing in my experience in third grade had warranted such terror, I had to consider the idea that I had scared myself – and done an exceptionally good job of it. At that point, the question evolved to: “How do I stop scaring myself?”

Life coach and writer Michael Neill describes the experience of fear (in this context) as analogous to someone drawing a picture of a monster, then running from the room terrified of it. Sometimes just realizing we’re the one doing the drawing changes the fear and our response to it. The psychological term, catastrophizing refers to a state of mind in which we magnify and make worse whatever is before us – kind of like drawing a monster. We may believe we have to be frightened, but it’s worth getting clear on our current premise, which lays the basis for what we perceive as impossible or manageable, dangerous or safe.

Years ago I was working on a children’s book, the premise of which was that the protagonist says “No” to everything, but after many drafts, I stopped making progress. The main character was facing obstacles but there was no movement in the emotional arc. It was only when I offered my protagonist a friendship she could not refuse that I understood the problem with the original premise. The story I wanted to write was actually about a girl who really wanted to say, “Yes”.

That shift in perception was liberating, and the book came together. We can do the same for our lives. We can embrace a premise that truly serves us – one that doesn’t make us hide or run or fight, one that doesn’t leave us frightened but, instead, engaged. We can create the story and life we most want.

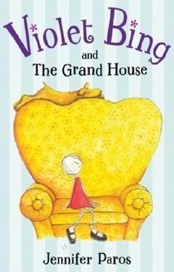

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.