Let the Story Unfold: The Dangers of Seeking Answers Too Soon

by Jennifer Paros

“And whether or not it is clear to you, no doubt the universe is unfolding as it should.”

For many years, whenever my husband went out and was the slightest bit late in returning, my youngest son would inevitably declare, “He’s dead.” It wasn’t just his father; he routinely came to this conclusion regardless of the person or circumstances. He was also quick to diagnose physical symptoms as cancer or, less specifically, something terminal. When we watched movies together, at the start of every film he would question why a character was upset or happy, ask what had happened, or demand explanations for just about everything. We encouraged him to wait and allow the story to unfold. There simply wasn’t enough information available to answer. But he continued asking – striving to pin things down that were still in the process of unfolding.

Watching my son rush toward answers (even unwanted and wrong ones) sheds light on how my own preoccupation with solutions and outcomes takes me out of the flow and into anxiety. I might believe it’s the unknown that’s causing my angst but, in truth, labeling uncertainties as “problems,” as well as the urgency to fix them, creates the distress and unease.

A bud needs time to open. There is no manual or mechanical method for expediting that process. It has to happen on its own using the natural intelligence that knows how to bloom. Noodling with it won’t help and most likely will hurt. We don’t call a bud a problem because it has yet to bloom. An experience can also be seen similarly – as in progress, in the process of blooming into the next thing. This is a less stressful way of receiving life and keeps us working with things rather than trying to fix them.

In my elementary school years, during gym class, we’d sometimes play softball. Often I’d end up in left or right field, far away from everyone, waiting and hoping no action would find me. I considered a soft ball high in the air on its way to me a problem. During those moments, I was out of flow – not because I wasn’t a great player (though I was not), but because “Don’t come to me; don’t come to me; don’t come to me,” is not the battle cry of a participant. I didn’t see opportunity; I saw a situation with an unknown outcome I believed might lead to me feeling bad. I was trying to pre-solve a possible problem in order to protect myself, instead of allowing the story to unfold and for me to open and grow with it.

“We must let go of the life we have planned, so as to accept the one that is waiting for us.”

We keep ourselves from finding and feeling our confidence. We might not even know it’s already inside us, believing instead that confidence has to be acquired rather than owned. Or, as in the case of the little boy, we might lose our sense of ourselves (where confidence lives) while temporarily hypnotized by the seeming pressure of the task at hand.

There is a term used in psychology: locus of control. It refers to the degree to which we think we have influence and impact on our lives. Personality types with an external locus of control believe luck or circumstances are determinant – that outside factors have greater power over their experience. Those with an internal orientation mainly believe their attitude, action, and focus affect their lives and ability to succeed. Internal locus types tend to be happier, higher achieving, have a strong sense of self-efficacy, and are physically healthier and more confident.

We are the instigators and activators of our confidence. That is control. When we believe the external world has more power over how we feel and live than we do, finding that seed of confidence becomes difficult. Locating confidence requires a pinpoint focus inward. We can teach ourselves how to find “home” – return to the core of who we are, and no longer look for self-assurance amongst the busyness, demands, and moving parts of life. We can reunite with the power and the readiness to break boards, paint pictures, write books, or whatever we wish.

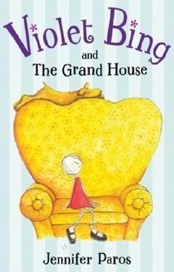

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.