Use It: No More Feeling Bad About It

by Jennifer Paros

“Concentrate on taking advantage of the crisis, using it as raw material with which to build something beautiful and good.”

As of late I’ve been harvesting my life for sore spots; I’m on a hunt for what snags me and sets off noticeable reactivity. I’m striving to pay attention to anything that inspires complaint or discomfort. I’m taking note of all my knee-jerk reactions no matter how small. I’m collecting this data, not as an indictment of myself or to create a therapy must-fix list, but because I’ve realized they’re clues. They are clues about patterns of thought that are working against me: the strategies of my personality, a personality that is admittedly delightful at times, and a bit of a pain, maybe even a nightmare, at others.

When I was younger, I didn’t know how to look at my negative reactions without feeling terrible about myself. I couldn’t step back from my thoughts. I didn’t want to be miserable, but certain situations seemed to require it of me. Still, just as everything I experience can be used as material for projects, inspiring and informing drawings and stories, life also provides experiences, thoughts, and feelings I can use for creating me.

To be able to step back from our thoughts, we have to know we have a choice in how we identify ourselves. Eckhart Tolle refers to the personality and the self-concept as the “form identity” and a deeper awareness as the “essential self.” The form identity gets hurt, is attached to conditions and outcomes, is easily affected and reactive, and works to protect its mental image of itself. When we begin to identify with our deeper self, we’re able to observe the personality patterns of thought that hold us back.

In writing memoir, the author becomes two: the writer self who holds the bigger picture and the character self in the story. As writers, we decide how to frame events, what to emphasize, and what to omit. We partially de-identify with our form selves in order to allow for the transformative qualities of the story to prevail. We don’t want the personality to tell the story; it’s too identified with what happened to it, its own opinions and judgments. The writer identifies with the essential self and has perspective – freed to express and use habits of thinking and feeling – to create something new, that would otherwise overwhelm the personality.

“You can be in touch with a deeper level of yourself where you can’t be hurt.”

Years ago, at a Sunday brunch, my father, my husband, and I were having a disagreement that became heated. Before we’d even eaten, my father announced he was going home, “If you don’t like my opinions, you don’t like me!” he said. He’d equated his ideas with who he was. I reassured him that we loved him; his mood softened considerably and he decided to stay. I didn’t love his opinion, but I saw the difference between what he was thinking and who he was – whether he could or not.

My youngest son, an adult now, was diagnosed on the autism spectrum when he was seven. He runs back and forth sometimes and usually makes sounds as he does so. It’s called “stimming” (short for self-stimulatory behavior) – an umbrella term that refers to repetitive activity and/or vocalizing. It’s considered a coping mechanism, a strategy for self-soothing. Through most of his teens he believed these behavioral patterns were who he was. But as the years have passed, he began describing the repetition as “exhausting,” and expressed his frustration with it limiting him in his life. He no longer believes the patterns are who he is; he’s come to perceive a self apart from the running. The identification with his essential self will enable him to use the running, and anything else that no longer serves him, to create what he really wants.

I have feared that the behaviors of which I am least proud are indicative of the person I am. But in truth, they are indicative of the person I am not. The pain I’m feeling at those moments is actually a byproduct of me not being true to me. The overreactions, upsets, and defensiveness are the habits and strategies of a self-image formed from habitual thinking – limiting only to one identified with it. But when we identify with a deeper self, it’s all material – information and clues for creating the most wonderful stories and the most beautiful lives.

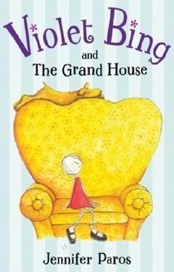

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.