Two Dreams and Three Deep Breaths: Learning to Be Still

by Jennifer Paros

“Being still does not mean don’t move. It means move in peace.”

The other night I dreamt of a bear. I am outside, and several yards away, a bear is holding onto the low branch of a tree. Upon seeing me, it releases the branch and starts to approach. I think to myself that when faced with a bear, one is supposed to stand still, but I cannot find the courage to do so, and hurry back to my cabin. Scrambling inside, I try to lock the flimsy door, but it seems the bear is now on the other side, pushing against it, making it hard for me to secure the bolt.

When I awoke, the first thing I wanted to know was the actual recommended protocol regarding real bears and the people who don’t want to be attacked by them. Depending on the type of bear, some say to make yourself as big as possible and make lots of noise, back up slowly while facing the bear, play dead or fight back, do not stare. Overall though, the advice seems to be: don’t run.

It’s not so easy being still when we believe something might hurt us. But learning to allow our minds to settle is the way through fear. When we take three slow breaths (with a longer exhale than inhale), it lessens the sympathetic nervous system’s fight or flight response and increases the parasympathetic nervous system’s rest and digest response, bringing the two into greater balance. This kind of breathing helps convince the sympathetic nervous system we’re not truly at risk, as it is counter to the shallow rapid breaths we’d be taking if we really were in danger. Our sympathetic nervous systems are set off by whatever we interpret as a threat, whether the thing actually is or isn’t. Without the perception of danger, no triggering of stress and the fight/flight response occurs.

We can learn how to make ourselves “bigger” than what we’re afraid of by remembering that we already are bigger – because we are the perceivers of the situation. The perceiver is the one telling the story; we’re the ones setting the tone – the hopefulness or the despair, as well as the point. The narrator creates the context in which the audience receives the unfolding events. We can own our bigger stature by purposefully embracing the responsibility and power of the role we already inherently play all the time, whether consciously or not.

“You’ve seen my descent. Now watch my rising.”

On election night I got myself twisted up in what ifs – possible outcomes I perceived as dangerous. I scared myself. Then I had to allow my thoughts to soften or they’d continue demanding my vigilance, which meant: no sleep. I started acknowledging all the wonderful things in life that would remain, regardless of who won, and managed to drift off. That night I dreamt of flying. In the dream I’m inside a big, old house where people have gathered together, mingling. I lift off the ground into the air and announce, “I figured it out! I figured out how to fly!” I explain that this is a dream and that I now know how to think in order to break from the illusion and operate outside of its rules. I fly up and down, forward and backward. I’m aware, though, that I still have to practice finding the focus that untethers me, allowing me to rise each time.

Every story creates a reality, in fiction-writing and in life. We tether ourselves to stories via our investment in their details. We can also use our attention to free ourselves at any moment. Nothing that comes along has to overwhelm us, not even the feeling of being overwhelmed. It’s okay to fall down; that’s what we tell our little ones. We downplay the falls because we want them to see themselves as resilient and recoverable. We tell a story that allows them to rise from the experience rather than being weighed down and tethered to the fall.

We have the power to allow a situation, our judgment of it, and any emotional reaction, to become muted in our experience. We can be still, and in our stillness know ourselves to be bigger than any story. The emotional charge diminishes and the situation no longer registers as a threat. We free our minds to operate outside the dictates of the current reality and the gravity of the story no longer has a hold on us.

We don’t need to run; we can rise.

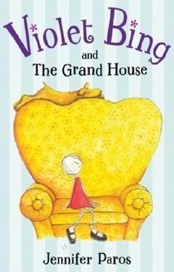

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.