Invisible Bones: Returning to the Center Spark of Your Project

by Jennifer Paros

“I shut my eyes in order to see.”

This year, in an unusual turn of events, I cooked a Thanksgiving turkey. Usually I bring side dishes and deserts and someone else makes the turkey. This time when I went to carve it – though I have hacked my way through the procedure before – I thought I’d shoot for better results. So I watched a YouTube video on How to Carve a Turkey.

As I attempted to apply the Turkey Carving System, however, I struggled; there seemed to be resistance on both the turkey’s and my part. I stopped and rethought my approach. I started paying more attention to the turkey’s design, using it as my guide. I followed its structure – places where it naturally gave and where it didn’t. As soon as I slowed down and paid more attention to the moment than the plan, the task got easier.

There is another kind of underlying structure and design to things not made of bones or other tangible parts. It’s an energetic anatomy that can provide us with a blueprint better than any how-to approach. In the field of astronomy, scientists have been creating simulations to try and “zoom” in on dark matter – the unseeable component that is approximately 83% of the matter in the universe. Dark matter is said to keep perceptible parts of the universe from flying apart via gravity. Currently, they understand it as like an “invisible skeleton” that serves as a framework for galaxies, stars, and planets.

I believe there are similar invisible bones underlying every creative project - every thing before it becomes a thing and once it’s in full form. As with dark matter and its role in the universe, the unseen designs of creative projects also hold worlds together, providing structure and support. But because we don’t witness them visibly, we have to learn to perceive them in a different way.

Several months ago I was working on a drawing and getting stressed about the deadline. Though I cared about the work, finishing it had become more of a necessary burden than a natural part of the creative process. I was critical of both the picture and me, increasingly resistant to working on it. Then one day, while striving to finish, I had the thought, It’s all for me. Though I’d be sharing the picture soon enough, everything I was doing, thinking, making, and livingwas first-off a gift for me. I had a good selfish interest in my work, one that I needed to remember.

“The object isn’t to make art, it’s to be in that wonderful state which makes art inevitable.”

This thought slowed the outward driven activity of my mind and placed my attention on the center spark of the project – its energetic pilot light – and my point of connection. When I switched from specific thoughts of doing to a general, receptive thought, inherently slower moving in nature, the pressure faded. I was able to work peacefully on the picture’s completion, now tuned to the whole of its hidden design and able to follow its lead.

The spark that starts a creative process always remains, but becomes hard to find when our focus is running around the perimeter of the idea. Once we let our thinking abate, it’s easier to locate that core light and blend our attention with it. Then our actions become inspired by it, not by intellectual conceptualization of what we think we ought to do and resistance to “having” to do it.

In the fictional mini-series, The Queen’s Gambit, chess prodigy Beth Harmon becomes addicted to tranquilizers, believing they help her envision moves and master the game. She takes the pills and watches the imagined pieces move themselves. With a tranquil mind, she allows herself to be guided by the invisible underpinnings of the game, led to intuitive discovery of what works and what doesn’t. With her full interest and intention, the chess pieces seem to find their own way, much like fiction writers allowing their characters to talk and storylines to unfold.

We have minds capable of focusing and perceiving in all different ways. Creating means working with the unseen and unknown – that’s what facing the blank page requires. Paying more attention to the moment than a plan, allowing our busy minds to slow, returning to the light at the center of the project, we can know without being able to see. We can trust and be guided by the invisible bones of our next creation.

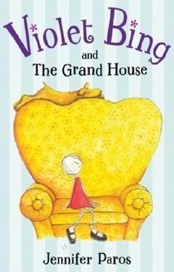

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.