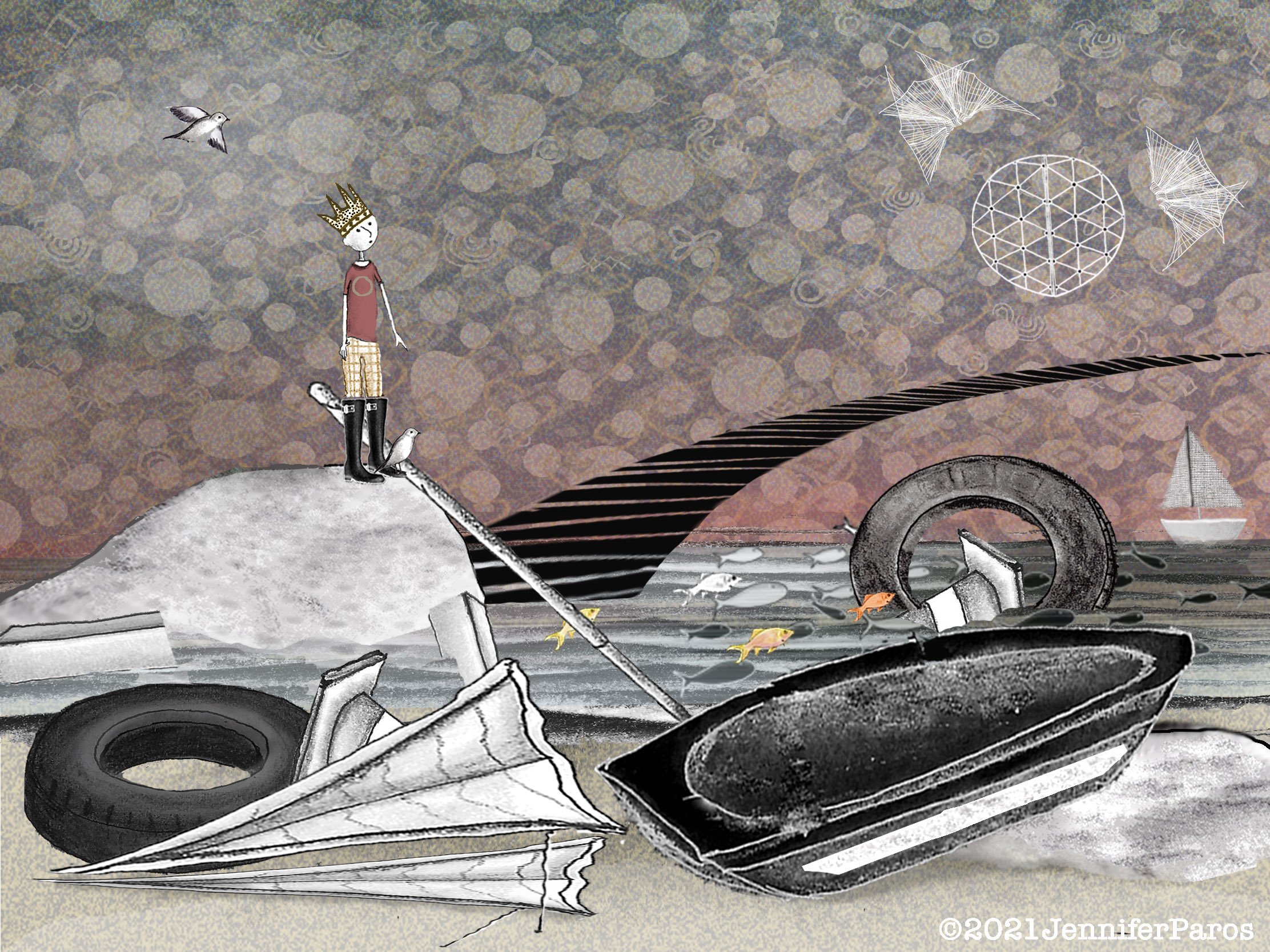

Our Path: Getting Over Obstacles, Resistance, and Retreat

By Jennifer Paros

“Most of us have two lives: the life we live, and the unlived life within us. Between the two stands Resistance”

When I worked at a daycare years ago, there was a five-year-old boy there named Phil. Slender and taller, with light blond hair and white, somewhat pasty skin, he often looked as though he’d been torn from bed only moments before arriving. Even while we were talking, I felt like I should be careful not to wake him. Phil seemed exhausted – if not by lack of sleep, then by lack of interest and the intrusion of the unwanted, bustling outer world. He often arrived in a worn t-shirt, pajama bottoms, and tall, black rubber boots, and would soon disappear into one of the play structures and remain there for, it seemed, as long as possible.

For those of us working at the daycare, Phil posed a bit of a challenge; we weren’t supposed to just leave him in a playhouse all day, playing by himself and dozing off. We were to try to draw him out. I identified with his resistance, the perpetual strike he seemed to be on, and the lure of hiding in small structures. But I also knew he wasn’t all that happy; that following the lead of resistance can afford us temporary relief but not actual happiness. Happiness is experienced when we we’re focused on our path, not what seems to be in the way of it.

In an article by writer and life coach, Martha Beck, her “6-Step Guide to Taming Your Fears,” the 5th step is: Watch the path, not the obstacles. She explains the difference between focusing on the way forward versus what we believe is in our way. Martha Beck’s hockey player friend explained it this way: when you’re taking a shot, you never look at the goalie but the space around him because the puck goes where your eyes go. And a whitewater kayaker told her to look at the water, not the rocks because “where your eyes go, the boat goes.” The advice seems obvious enough, but when there appear to be obstacles and possible dangers, it can easily feel necessary for us to try to avoid them, fight them, or get over them, which means our attention is on them -- taking us off track.

When we write, we have to go where we want to go in our imagination, then translate it for the reader. I was recently working on a fictional piece and found myself thinking, “This story is too sad.” I’d isolated something unwanted and now my focus was on trying to avoid it. I was perceiving my judgment as an obstacle, not just a thought. After all, who wants to read a story that’s “too sad”?This story is too sad is a thought that immediately undermined my efforts to write it.

“Art is nothing but the expression of our dream; the more we surrender to it the closer we get to the inner truth of things, our dream-life, the true life that scorns questions and does not see them. ”

I had to decide whether I was going to focus on my negative assessment (off the path) or on the open mental space around it (the actual path). Often, we’re inclined to take our judgments very seriously and believe they must be acted upon immediately, which would mean, in this case, trying to make the story happier or junking it altogether. However, there is always a life to our work, that exists beyond assessments, that serves as a much better guide. All the ideas and characters in the story that I love indicate the path and are at the creative center of the work. I can let them call me through the process rather than being directed by a fixation on where I don’t want to go. Though the usual approach involves isolating what’s wrong and then trying to fix it, a “fix” truly works only when inspired by what the story actually wants to be and authentically is.

Like Phil, when faced with something unwanted, my inclination is often to resist or retreat. But there’s never enough life inside a hiding space. And when we hide from what we don’t want, we end up hiding from what we do want as well. It’s our job. when creating, to rest in the story we most want to tell, not to wage a war or run from what we believe is in our way. We surrender to what we love.

And when we do that, we allow ourselves to be naturally and happily led out and forward to what we most want.

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.