Bigger Than Death, Larger Than Life: Embracing Our Greater Value

by Jennifer Paros

“We are in a constant state of transformation.”

My father died recently. He was eighty-five years old and died in his sleep. When we arrived at his house, the police officer told us we could look at the body if we wished. The emergency care workers had laid it on the floor in his bedroom. After some time, I walked up the steps and peered in from the doorway. There it was – covered with a sheet – and the first thing I thought was how very small his body was – much too small to have housed him.

All that intelligence; he was an idea-, word-, movie-, book-loving, writing, teaching, leading director of all sorts with an unrelenting persistence and stubbornness. Everything I knew about my father, which was certainly not his totality, must have streamed through his physical self but couldn’t have been contained in it.

It made me think of neuroscientist Jill Bolte Taylor’s 2008 TED Talk in which she describes suffering a hemorrhage in the left hemisphere of her brain. Her language-centers, memory, and logic gradually went “offline.” She describes being unable to define the boundaries of her body – seemingly blending molecularly with her environment and losing her personal identity. She says she knew a great peacefulness. “I felt enormous and expansive, like a genie liberated from her bottle . . .. I remember thinking there’s no way I would ever be able to squeeze the enormousness of myself back inside this tiny, little body.”

The fact that my father was in that body in the first place, and then managed, like Houdini, to escape, seemed remarkable. Death is mostly considered an awful thing, but it felt magical to me. And just as in magic tricks, the audience is both perplexed that the magician has disappeared, but also knows he is still around – somewhere.

Not too long ago, my father told me he was afraid of being irrelevant (his word). I replied that we are all inherently relevant. Accomplishments can be wonderful, and sometimes even a great service, but our relevance does not depend on them. Having held my sons when they were newborns, I’ve never been able to shake the knowledge that everyone comes in valuable and that that value does not diminish. And what is valuable is relevant. But my Dad hoped to know his relevance through external recognition, though his true relevance was so much greater than any work he did and any recognition he received.

“Love is anterior to life, posterior to death, initial of creation, and the exponent of breath.”

In Oprah’s recent interview with Timothy Shriver, Chairman and CEO of Special Olympics, he describes growing up in the Shriver family and their intense drive to do, accomplish, and serve. But Shriver wanted to know his worth apart from performance. It was his exposure to Special Olympics (founded by his mother, Eunice Kennedy Shriver) and his time spent with his cousin Rosemary who, herself, had a mental disability, that taught him about human worth far beyond achievement. Shriver explains how people with special needs don’t usually meet society’s definitions of “pretty”, “accomplished,” or “smart” – everything we’re told is important and makes us relevant. Yet from working with those with special needs he’s coming to understand the greater value inherent in all of us. When asked what lesson he is still striving to learn, Shriver replied: “I matter regardless of what I do.”

An old college boyfriend contacted me years ago and the first thing he did was send me what seemed to be a resume. He was a musician, composer, and teacher, and there in a dense, long list was (seemingly) every country to which he’d traveled, each time he’d performed, every place he’d taught, everything he’d done. I didn’t bother reading it all. I had cared about him long before all of that. What he’d accomplished did not make him more important or relevant to me; he just was – naturally.

Love is a divine property, unprovable and endless. It inspires all the wonderful actions and creations in the world, and it flows through us whenever we allow it. It has no place on a resume, but it remains the greatest determining factor of just how much of ourselves we express. We can make and do fantastic things. Sometimes we mistake our accomplishments for our value. But it is the force of love behind those accomplishments and us that is so much bigger than death, and so much larger than these little lives could ever be.

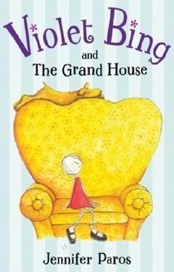

Jennifer Paros is a writer, illustrator, and author of Violet Bing and the Grand House (Viking, 2007). She lives in Seattle. Please visit her website.