The Drive To Publish and Other Existential Dilemmas

By Pamela Jane

Growing up, I pondered compelling questions, such as: What is real? What if the physical world were merely a curtain on which air, sunlight, and even time were painted? Even my own existence might be an illusion.

As a small child, I couldn't articulate my existential worries. This made me feel even more insubstantial.

It's not like my parents said, "Wow! You're thinking big thoughts! Finish your Frosted Flakes. Then we'll talk about the illusory nature of reality." They were too busy with their own lives. My second grade teacher, Mrs. Greer, wasn't any help either. She was busy assigning story-problems about children going to the store to buy candy. Just when you were getting interested in the candy-store adventure, they presented you with a math equation involving personal liquidation. Consequently, I lost all trust in teachers and interest in school. But internally, I kept working furiously on my existence dilemma.

The only way I could prove that I existed, or at least increase the odds, was if others – thousands of others – acknowledged it, as if I could certify my existence by how many opted in. I envied kids on family sitcoms like Leave it to Beaver. No one could dispute the fact of their existence; it was right there on the television screen!

I decided to star in my own imaginary sitcom beamed into millions of homes across the country. I made a secret hand gesture to signal when I went on air.

"Mom, tomorrow is Valentine's Day!" I called aloud. “Are you going to give Dad something special?"

"I hadn't thought about it," my mother replied.

"How about making Valentine cupcakes with pink frosting?"

"That's an idea."

Perfect! Kids all over the country were glued to the TV, watching to see what would happen next. Of course, the cupcake-surprise would be a disaster, (oops, mom used salt instead of sugar!) but we'd be laughing by the time the end credits rolled.

Inevitably the action was interrupted by unapproved dialogue changes on the part of my parents.

"Phil, you told me you had stopped smoking!"

"Oh, for Chrissakes, Marge, stop badgering me."

Cut to an ad, quick!

"Tostitos brand tortilla chips are perfect for sharing with friends..."

I couldn't keep breaking for ads though. It might be easier, I thought, to become famous as a detective, like Nancy Drew, who won the respect of her distinguished father with her quick-wittedness and courage.

There had recently been an attempted kidnapping in the next town. My friend, Jen, and I combed the neighborhood searching for clues to the kidnapper's identity – a scrap of paper, a suspicious footprint, a dropped glove. But nothing panned out. Then one night, a car slowed down on our street. Quickly and resourcefully, I jotted down the license plate number. Then the mysterious automobile sped away!

We waited for the next episode to unfold, but nothing happened. There was no second chapter, no subsequent clue. Nancy Drew never had to face having the entire plot line collapse around her.

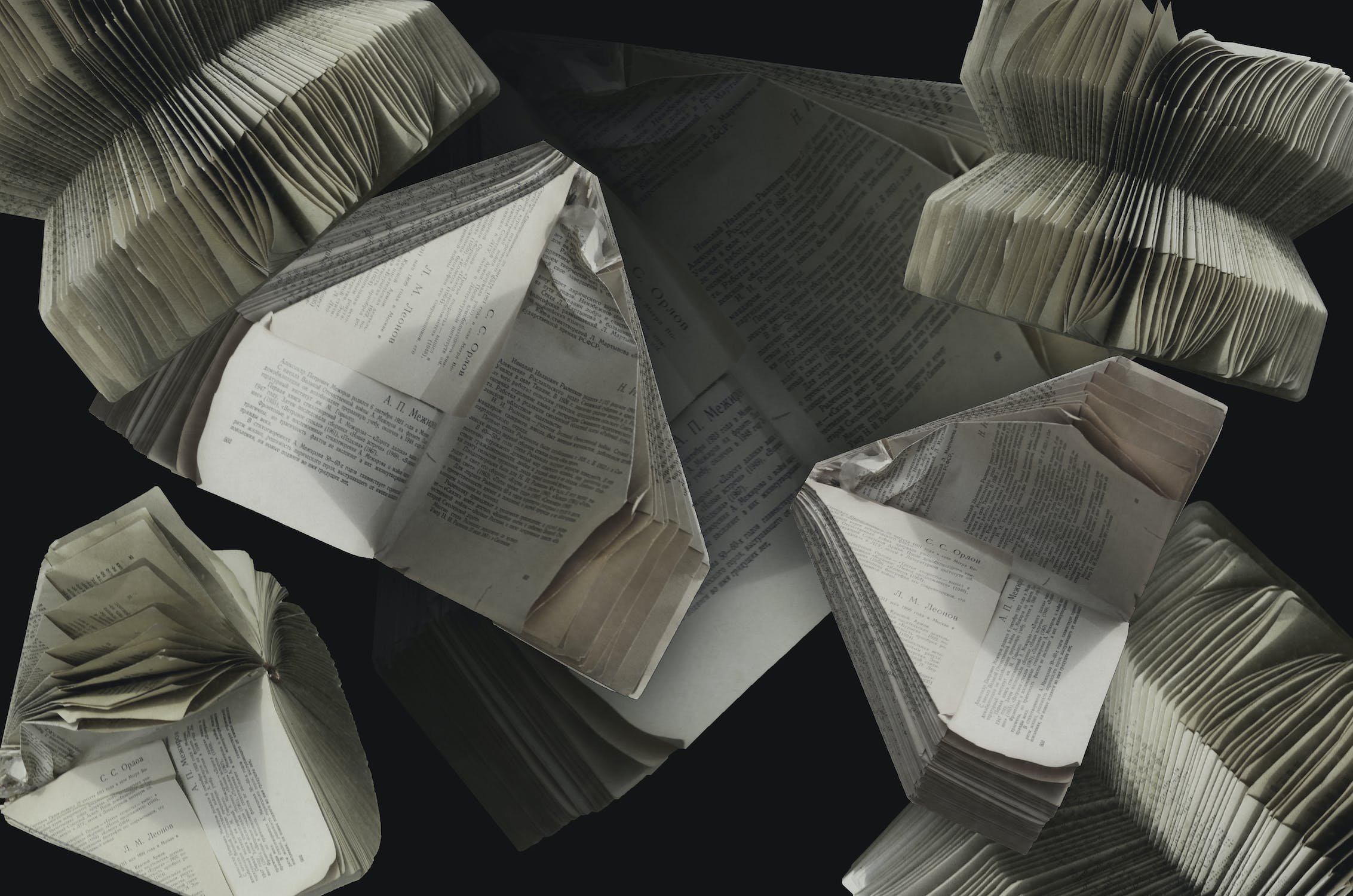

It was time to seize creative control. I decided to write a book in my head. Most books, I noticed, left out interesting details, like blinking and going to the bathroom. My book would include everything. All over the world, people waited breathlessly for the next installment. The small dramas of day-to-day life were not obscure, unrecorded episodes in the life of a little girl, but events of universal interest and importance.

I must have been churning out a thousand pages of imaginary manuscripts a month, when something happened that caused my interior printing press to jam.

"We're moving," my mother announced, without warning.

"Why?" I asked, stunned. Moving wasn't written into my plot synopsis.

"Berkley is ugly," my mother said simply. "We're moving to a nicer town with better schools."

Better schools? As far as I was concerned schools were forced labor camps that robbed me of precious time to work on my existence theorem. And for this my parents were yanking me out of my story, precipitating an existential crisis for my character and leaving my massive worldwide readership hanging?

The books in my head did indeed go out of print after our move, in spite of the fancy forced labor camps with creative writing classes and swimming pools. Eventually, I gave up trying to prove I existed, and became a children's author. Eventually I gave up my childish dreams of universal fame and worked to become a children's author.

In a sense, all creative expression is an attempt to prove one's existence, but it wasn't until I wrote a memoir that I made a serious effort to climb back into my internal narrative. Publishing a memoir was a last-ditch effort, a desperate swing to grab hold of the perilously slippery "I" – one that raised more questions than it answered. Who was the "I" dictating, and who was dictating to it?

Some people have the drive to procreate; I have the drive to write and publish. But does it make sense to have my existence contingent on publishing a memoir or an op-ed in The New York Times? What if their ad revenue falls, or their subscription sales decline? Would that put me in existential peril? Is ThriftBooks proof of an afterlife?

I think I'll go back to writing in my head. The books in my head top the best-seller lists and spawn a glittering array of film and TV spin offs. There are no bad reviews, books that bomb, or snarky "verified purchase" comments on Amazon.

All I have to worry about now is the cover price.

Pamela Jane is an author of over thirty children’s books, including Little Goblins Ten (Harper) about which the NYT wrote, “The classic counting rhyme ‘Over in the Meadow’ goes spooky in this Halloween riff." Pamela has published essays in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Next Tribe, The New York Daily News, Writer's Digest, The Independent, and The Writer. On her book with coauthor Deborah Guyol, Pride and Prejudice and Kitties: A Cat-Lover's Romp Through Jane Austen's Classic (Skyhorse), ALA wrote, "We give you Jane Austen and cats, and that means we're in it for the long haul.”