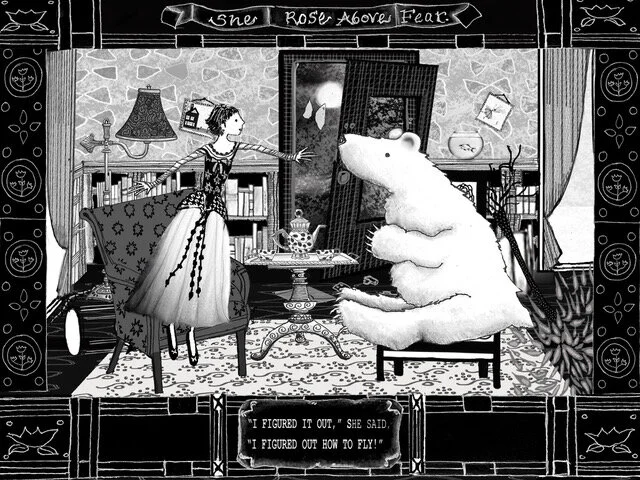

he other night I dreamt of a bear. I am outside, and several yards away, a bear is holding onto the low branch of a tree. Upon seeing me, it releases the branch and starts to approach. I think to myself that when faced with a bear, one is supposed to stand still, but I cannot find the courage to do so, and hurry back to my cabin. Scrambling inside, I try to lock the flimsy door, but it seems the bear is now on the other side, pushing against it, making it hard for me to secure the bolt.

When I awoke, the first thing I wanted to know was the actual recommended protocol regarding real bears and the people who don’t want to be attacked by them. Depending on the type of bear, some say to make yourself as big as possible and make lots of noise, back up slowly while facing the bear, play dead or fight back, do not stare. Overall though, the advice seems to be: don’t run.

It’s not so easy being still when we believe something might hurt us. But learning to allow our minds to settle is the way through fear. When we take three slow breaths (with a longer exhale than inhale), it lessens the sympathetic nervous system’s fight or flight response and increases the parasympathetic nervous system’s rest and digest response, bringing the two into greater balance. This kind of breathing helps convince the sympathetic nervous system we’re not truly at risk, as it is counter to the shallow rapid breaths we’d be taking if we really were in danger. Our sympathetic nervous systems are set off by whatever we interpret as a threat, whether the thing actually is or isn’t. Without the perception of danger, no triggering of stress and the fight/flight response occurs.

Read More